This paper was first presented at The First World Olympic Congress of Philosophy in Athens-Spetses, from June 27th to July 4th, 2004.

By Pierre Grimes, Ph. D.

Revised for the web by Sean P. Orfila

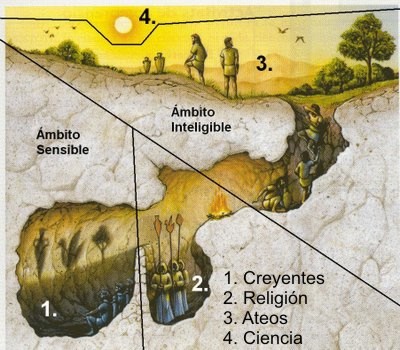

The shadows on the wall in Plato’s Allegory of the Cave and the Upper World are the man-made icons of man that we have been led to believe are our ideals, but they are merely shadows of justice flickering on the wall of the cave.

The mystery we will explore is why we accepted images for our reality and why they have the power to transform our lives. The craft that fashions and supports these images are the work of sophistry.

The issue before us is to discover how we were persuaded to believe as true what is manifestly false and how we can learn to be free of such sophistry.

Challenging such sophistry is the time-honored goal of Platonic philosophy and it is this that makes Philosophical Midwifery a major part of a philosophy whose goals are at once spiritual and rational.

The good life is open to all through the participation in mind for this is what illumines our struggle to achieve our highest and most profound excellence, arete.

It is natural to encounter difficulties in this struggle and, indeed, they must be overcome if the excellence we seek is to be achieved, but these difficulties are termed problems–or the pathologos–only when they block one from achieving that excellence.

The pathologos, or blocks, have their roots in the false beliefs we have accepted about ourselves and the nature of our reality, and they are inimical to and irreconcilable with one’s higher and more profound goals.

They function as a monad in that they link with others, becoming a key component of the image of the self, and appearing cyclically throughout one’s life.

Since we have convinced ourselves that these images are true, we have effectively blocked ourselves from our own meaningful goals. Thus, we can say that we have trapped and fettered ourselves in the cave of our own minds.

To free ourselves of such false beliefs it is essential to discover what made them believable and to learn the conditions that were necessary for us to assume they were true, and then to learn how they were communicated to us.

Further, we need then to see clearly what maintains their influence into the present, and, finally, see what ends their strange power over us. These are the goals of Philosophical Midwifery, an adaptation of the Socratic art and a rational method for resolving these kinds of blocks and bringing about a new paradigm for understanding human problems.

Philosophical midwifery, as a mode of Philosophical Practice, is a non-interpretive dialogical exploration that has been taught and practiced for overcoming the blocks in the struggle to the achieve excellence.

The method of PM surfaces these pathologos-beliefs, discovers what factors made them believable, accounts for what maintains them and, in recognizing the way they function, brings about their dissolution.

As a result, the method of PM brings about an understanding of the significance of functional understanding, and in doing so, ends the suspicion that mind is incapable of understanding its own problems.

—–

From the viewpoint of Philosophical Midwifery, the class of human problems that manifest themselves in the pursuit of one’s highest goals are the result of the transmission of early learned false beliefs of the family-clan.

These conclusions become a central part of the child’s limited self image. The timing of the imposition for the transmission is when the child innocently, and in an open and receptive state of mind, violates or goes beyond the boundary of the image that the family-clan has of themselves and their place in the world.

The transmission scenes are carefully selected so that parental figures, or their surrogates, can give their most convincing appearance of being sincere, caring, and knowing, which for the child, then becomes the model for love, caring, and knowing.

The function of the transmission scene is to bring the subject to voluntarily forfeit their own personal goals for freedom and accept the family-clan boundary as their reality.

In accepting this limitation of their exercise of freedom, the child plays out their role within the family-clan goals.

The volition of the child is captured and the subjugation is complete, as the child unknowingly exchanges their newly found sense of freedom for the sense of belonging to the clan.

The price for the deception is their loss of freedom, and with it, their own experience of integrity. There is no need for violence or punishment in these scenes, since they are carefully designed only to convince the child to abandon their own direction and to live within the confines of acceptable belief.

In sharing their fundamental concerns, the parental figures must appear their noblest and most sincere so that the picture they present of themselves is one of being virtuous, and of being just.

When those we respect and idenify with are willing to appear before us as most virtuous and just, having seen nothing more noble than this, we accept that as our ideal.

In seeing those we love sharing with us what they love and what they have learned about life, we believe the truth of what they say and we are converted to their beliefs.

The image of justice they hold up before the child is accepted as real. The child forfeits her freedom, and assumes a role within the limits of the family image and defends it loyally, and is willing to sacrifice all for that shadow of justice.

Curiously, the origin of vice lies in modeling oneself after the image of justice, not its reality, and in making others pay dearly for threatening the status of that belief.

However, in some deep way the child always knows that they have been compromised and that is the origin of the sullen rage against authority.

Thus, while the child gains acceptance within the family-clan structure, the price the child pays is not to question the process, since the examination of its origins would surface the grounds of its acceptance.

Agreeing, if even implicitly, to the curtailing of the mind from any examination of this belief structure becomes an avoidance and fear of the cultivation of the mind.

The loyalty to the pathologos belief becomes a badge of honor and whenever circumstances are sufficiently parallel, or analogous, to what was transmitted in these past learned scenes, the believer will defend vigorously, believing it to be an attack against their own cherised ideal of justice.

It is experienced as an affront against their honor, and it justifies their seeking for ruinous revenge.

The suffering, the grief, and turmoil that spins out from revenge is the cycle that begins with anger. It is through the exploration of the dynamics of the cycle of anger that we can gain insight and understanding of pathologos problems.

—–

When the believer is brought to see the full consequences of their pathologos-belief, they experience a deep and profound shock.

If the believer can then bring themselves to see that the tragic circumstances of their life was the consequence of blindly adhering to their false belief, then it is possible for them to emerge from the shadows of belief and test their understanding in those very situations that previously blocked them.

If this is achieved, the believer becomes a new person with a new vision of life.

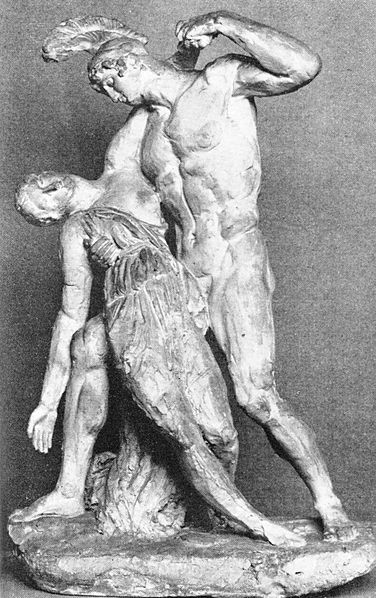

This is the story of Achilles. Achilles was able to move out of the fury and turmoil of rage and revenge and into a mindful excellence.

Other classical authors have recognized that underming a child’s self—both their image and their belief system — brings about social and individual chaos.

In Plato’s Republic, the fall of the aristocratic state is caused by members of the ruling family undermining the child’s self image and his perception of his father.

While Plato does not offer any insight into why such sophistry became believable to the child, he does capture the circumstances of the transmission of that idea.

Indeed, one of the central philosophical issues explored in the dialogues of Plato is the unmasking of the sophist as a pretender to knowledge. As the high point of the sophist’s art is fashioning irrational beliefs so as to appear acceptable to the believer, as if they are rational and true–so the unmasking of the sophist as a pretender to knowledge falls within the art of the philosopher.

—–

There are few authors who have been able to depict with sufficient scope and precision the dynamics of belief formation so that others can recognize the rationality behind this little understood phenomena.

However, we shall see that Homer’s work does have the scope and precision we require, since the goal of his Iliad is to understand the wrath of Achilles and to understand how that anger fulfills the will of Zeus.

Homer brings us to see that behind Achilles’ anger it is possible to understand the dynamics of the origin and dissolution of his ruinous false beliefs about himself.

He traces the origin of his fury to his early learning experiences, and once Achilles was able to reject the powerful influence of his early learned false beliefs, he was able to become truly heroic and to achieve human excellence.

In chosing Achilles’ problem to explore we are selecting a problem we all share, since similar dynamics as those behind Achilles’ problem exhibit themselves in our own lives as well, even though they may not take on the extreme form as they did with Achilles.

For just as the blinding rage that Achilles felt over experiencing injustice kept him from seeing its destructive folly, so too we are blinded by our own feelings of resentment and revenge over the injustices we have experienced in our own past.

The perpetuation of these sullen grievances diminishes our capacity to enter into mindfulness. To further our analysis we shall turn to Homer’s Iliad, where we may demonstrate that Homer’s understanding of human nature is consistent with PM.

We found that by applying this paradigm to those who explore human problems, we can determine the level of rationality of their methods and work, both in the past and present.

There is a particular and interesting challenge in applying these principles to Homer’s Iliad, because we can be brought to see that in Achilles’ struggle to overcome his blocks, Homer not only traces nearly all the stages of uncovering and resolving problems outlined in philosophical midwifery, but he includes a stage that was also overlooked prior to this study of Homer…

This paper continues into a proof that demonstrates Homer’s Illiad as a mode of Philosophical Midwifery. If you’d like to receive the paper in full, please contact us.